Biography

Christian Steven Hoggard is a computational archaeologist and Senior Data Insight Analyst at the University of Southampton (UK). Christian is interested, and has published on, quantitative approaches to the past, focusing on phylogenetic and morphometric approaches to artefact variation. Christian is also interested in R-based approaches to data science, specifically data transformation, analysis and data visualisation.

- R-Based Data Science

- Quantitative Archaeology

- Cultural Evolution

- Data Visualisation

PhD Archaeology, 2017

University of Southampton

MA Palaeo. Arch. & Human Origins, 2013

University of Southampton

BA (Hons) Archaeology, 2012

University of Southampton

Skills

inc. RMarkdown and RSQLite

inc. statistics and machine learning

inc. R, HTML and CSS

Experience

Featured Publications

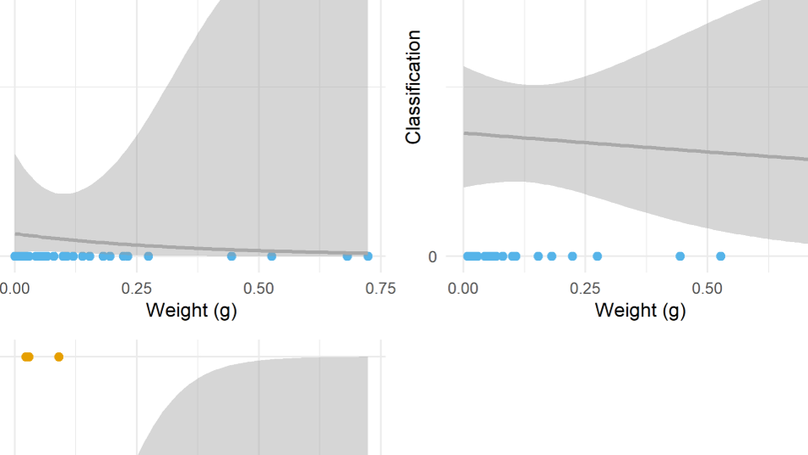

The retouching and resharpening of lithic tools during their production and maintenance leads to the production of large numbers of small flakes and chips known as microdebitage. Standard analytical approaches to this material involves the mapping of microartefact densities to identify activity areas, and the creation of techno-typologies to characterise the form of retouch flakes from different types of tools. Whilst use-wear analysis is a common approach to the analysis of tools, it has been applied much less commonly to microdebitage. This paper contends that the use-wear analysis of microdebitage holds great potential for identifying activity areas on archaeological sites, representing a relatively unexplored analytical resource within microartefact assemblages. In order to test the range of factors that affect the identification of use-wear traces on small retouch flakes, a blind test consisting of 40 retouch flakes was conducted. The results show that wear traces can be identified with comparable levels of accuracy to those reported for historic blind tests of standard lithic tools suggesting that the use-wear analysis of retouch flakes can be a useful analytical tool in understanding site function, and in increasing sample sizes in cases where assemblages contain few tools.

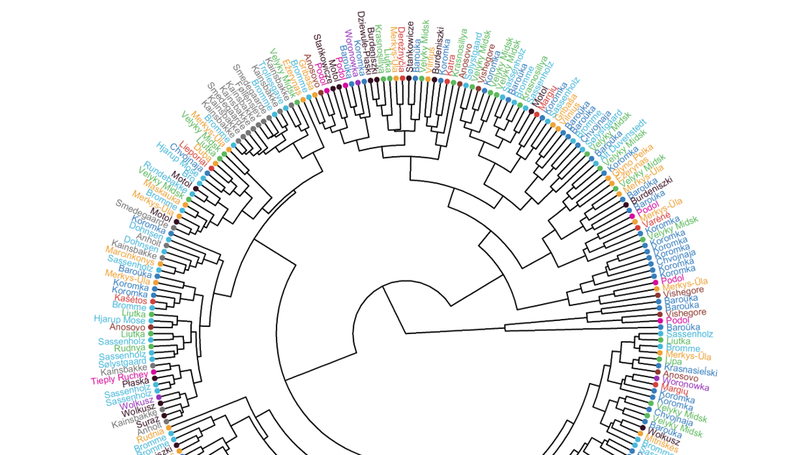

The Late Glacial, that is the period from the first pronounced warming after the Last GlacialMaximum to the beginning of the Holocene (c. 16,000–11,700 calBP), is traditionally viewed as atime when northern Europe was being recolonized and Late Palaeolithic cultures diversified. Thesecultures are characterized by particular artefact types, or the co-occurrence or specific relative frequenciesof these. In north-eastern Europe, numerous cultures have been proposed on the basis of supposedlydifferent tanged points. This practice of naming new cultural units based on these perceived differenceshas been repeatedly critiqued, but robust alternatives have rarely been offered. Here, we review thetaxonomic landscape of Late Palaeolithic large tanged point cultures in eastern Europe as currentlyenvisaged, which leads us to be cautious about the epistemological validity of many of the constituentgroups. This, in turn, motivates us to investigate the key artefact class, the large tanged point, usinggeometric morphometric methods. Using these methods, we show that distinct groups are difficult torecognize, with major implications for our understanding of patterns and processes of culture change inthis period in north-eastern Europe and perhaps elsewhere.

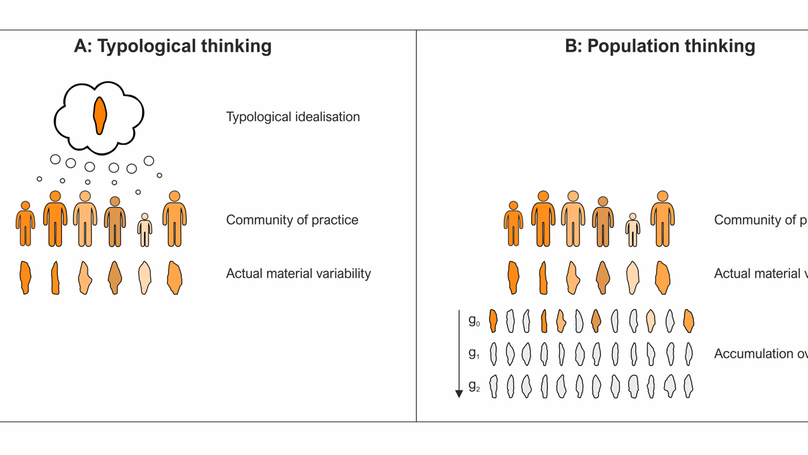

The analysis of ancient genomes is having a major impact on archaeological interpretations. Yet, the methodological divide between these disciplines is substantial. Fundamentally, there is an urgent need to reconcile archaeological and genetic taxonomies. However, traditional archaeological taxonomies are problematic because they are epistemologically weak and often laden with undue assumptions about past ethnicity and demography—they are a hindrance rather than a help in such a reconciliation. Eisenmann and colleagues have recently tackled this issue, offering a palette of potential solutions that circumvents traditional archaeological culture labels. We welcome renewed attention to nomenclature but take issue with such recent work that favours systems of taxonomic assignment for genomic groups that either do not include archaeological information at all or retain traditional cultural taxonomic categories. While superficially pragmatic, these administrative solutions do not address the substantive issues that the topic raises. We here present the argument that the only analytically viable solution to aligning genetic and cultural nomenclature is to conceptualise material culture as underwritten by a system of information transmission across generations that has similar structural properties to the genetic system of information transmission. This alignment facilitates the use of similar analytical protocols and hence allows for a true parallel analysis. Once culture change is also understood as an evolutionary process, a wealth of analytical methods for reconciling archaeological and genetic clusters becomes available.

Recent Publications

Contact

- C.S.Hoggard@soton.ac.uk

- University of Southampton, Southampton, Hampshire, SO17 1BJ